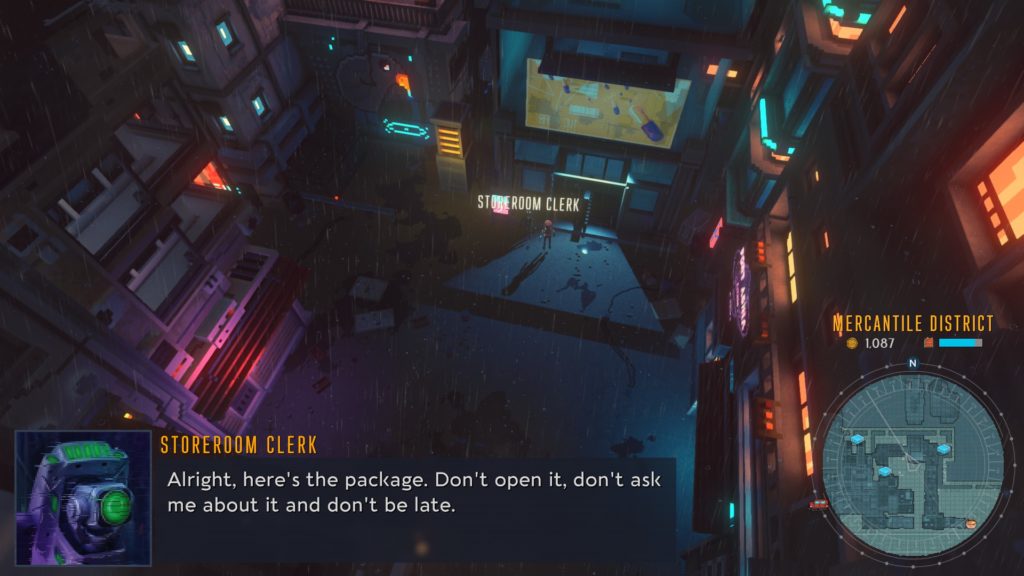

Like Paperboy, Farming Simulator and Tokyo Bus Guide before it, Cloudpunk is an example of what some academics have termed “playbour”: video games that attempt to convert the rhythms of work into the substance of play, to transpose the workstation to the playstation, as it were. But as well as the games that enable us to become racing drivers, fighter pilots and hoorah’ing marines, there is an alternative stream of play where the games are based on working-class labour. One of the attractions of the video game medium has always been the opportunity to taste, first-hand, experiences, places or roles that are too dangerous, remote or fabulous for reality. You might hear a package ticking on the back seat, forcing you to make a snap decision But Cloudpunk also slips the constraints of its genre by virtue of its casting: you play, not as a monosyllabic hacker trying to topple a megacorp, or as an ex-cop trying to win back his badge, but as that humble hero of the hour: the delivery driver. The buzz when you first realise you can park up and gather them up on foot is exhilarating. As you sweep across its glowing vistas, weaving in, out, over, and under the local traffic, the tumbling blocks of houses below appear to plead to spill their secrets. In part that’s because this is a world constructed from tiny pixelated building blocks, which give the city and its distinct districts the feel of a basement Lego project that got wildly out of hand. Still, overfamiliarity with the aesthetic does little to blunt the fierce appeal of Cloudpunk’s game world. With its streaking hover cars and pink-humming katakana signs, the sparkling rain and homeless androids, it’s a cliche that invites cliches: “sprawling”, “neon-lit”, “ Blade Runner-esque”. T he city of Nivalis is, at once, arrestingly beautiful and awkwardly familiar.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)